LBO vs CRE Acquisition Models and Using LBO Structure to Acquire CRE

In the world of investment and finance, models play an integral role in guiding decision-making processes, evaluating risk, and forecasting returns. Two such influential models are the Leveraged Buyout (LBO) Model and the Commercial Real Estate (CRE) Acquisition Model. Both aim to guide acquisitions in a unique way that reflects their different underlying assets and objectives.

Incorporating an LBO structure into CRE acquisitions represents a strategic approach to unlocking value and maximizing returns on investment. By leveraging financial engineering principles, investors can achieve a delicate balance between debt and equity, fostering financial flexibility and the potential for substantial returns. However, it’s crucial for investors to conduct thorough due diligence, implement effective risk management strategies, and adapt to changing market conditions to ensure the success of LBO-structured CRE acquisitions. As with any investment strategy, careful consideration of risks and opportunities is paramount for achieving long-term success.

This article delves into the specifics of LBO and CRE models, compares their structures, and discusses how synergizing them can lead to a more robust investment strategy.

Note from Spencer and Michael: This is another post from our guest contributors and industry professionals. With a CFA, engineering background, and MBA, Muhammad Shahzad Khan brings deep expertise in Leveraged Buyouts, Real Estate, and Project Finance. Currently at Ahli Bank in Oman, his rich experience as an investment leader is an invaluable asset. We’re grateful for his insights shared with our community. Click here to learn more about Shahzad.

Introduction to the Models

LBO Model

A Leveraged Buyout is the acquisition of a company or assets of a company, primarily using debt for financing. This model determines the expected return on equity from the purchase price, financing structure, and exit strategy. Its central principle is to use high levels of debt to finance acquisitions, with the expectation that the cash flows will suffice to service this debt, thereby increasing the equity component and returns.

However, not every acquisition with tons of debt is classified as Leverage Buyout. For LBOs, there must be a Company / Private Equity Investor (PE Investor) who buys the target company with the intention to sell in the near future (10 years or less). Companies with an intention to hold for long term, in a value chain to control input/output or horizontally to increase production and reduce competition, are classified as normal M&A transaction.

Investors in an LBO transaction hope to create value through three sources: (a) Business Growth, (b) Multiple Expansion (EV/EBITDA, Price/Revenue etc.) and (c) Debt Reduction. The ultimate objective is to receive the highest possible price at the exit and maximize IRR. If the investment is successful, the combined effect of these reaps a very high return for the equity investors.

CRE Acquisition Model

Commercial Real Estate Acquisition Models focus on acquiring real estate assets. It evaluates the potential return from such acquisitions based on factors like purchase price, expected rental incomes, property appreciation, maintenance costs, and the eventual sale of the asset. Here, the focus is on cash flows generated by the property and the appreciation of its inherent value over time.

Key Differences Between LBO and CRE Acquisition Models:

| LBO Model | CRE Acquisition Model |

| Asset Type | |

| LBOs typically involve the acquisition of entire businesses, transitioning public companies into private entities, or acquiring specific assets through stock or asset purchases. | CRE focuses on real property. Essentially, it is an asset purchase transaction. |

| Financing Structure | |

| LBOs are characterized by a high level of debt. | The acquisition of CRE can be financed with or without debt. |

| Cash Flows | |

| Cash flows arise from business operations: increased sales, cost efficiencies, and potential synergies. | Cash flows stem from property rentals, leases, or operational incomes like parking fees. |

| Time Horizon and Exit Strategy | |

| LBOs typically come with a defined short to medium term exit plan. They often involve strategies like IPOs or selling to other investors. Given the elevated levels of debt, LBOs carry heightened financial and operational risks, emphasizing the need to minimize leverage. | The holding period for CRE can be medium to long term and exit depends on real estate market fluctuations, property-specific issues, and macroeconomic factors affecting property demand and valuation. |

Synthesizing LBO and CRE Acquisition Models for Enhanced Structure

When considering combining the strategies of Leveraged Buyouts and Commercial Real Estate Acquisitions, it’s essential to recognize that it isn’t about blending two unrelated investment mechanisms. Instead, it’s about leveraging the inherent strengths of each model to offset the weaknesses or challenges of the other. This can create a more holistic, diversified, and potentially more stable investment strategy. Here’s how:

Diversification

One of the cardinal rules of investing is ‘don’t put all your eggs in one basket.’ By employing both LBO and CRE strategies, investors can spread risk across business acquisitions and tangible real estate assets.

LBOs involve acquiring businesses or segments of companies. A myriad of factors can influence these acquisitions, including market competition, regulatory environments, consumer behavior, and technological advancements.

Contrastingly, CRE involves tangible real estate assets. Factors like location, real estate market trends, and macroeconomic indicators influence the intrinsic value of assets.

Enhanced Cash Flow Management

LBOs, given their high debt levels, need efficient cash flow management. A stable CRE asset with consistent rental yields can act as a hedge, providing consistent cash inflows to service LBO-related debt.

LBOs, because of their high leverage, require consistent cash inflows to service the debt. However, businesses often face cash flow fluctuations from various operational challenges. CRE assets, especially those with long-term lease agreements, can provide steady cash inflows from rent.

When intertwining these strategies, you can reduce the risk of defaulting.

Capital Appreciation and Value Creation

In LBOs, the aim is often to improve the operations of the acquired company and increase its value. This could involve tapping into new markets, streamlining operations, or leveraging synergies.

CRE acquisitions focus on both rental yields and capital appreciation of the property over time.

An intertwined strategy could involve using a property’s appreciated value (from the CRE model) to fund expansion activities or new ventures for the company acquired in the LBO. You can leverage the capital appreciation from one asset (real estate) to enhance the value of the other asset (business operations).

Collateral Benefits

Real estate assets have tangible value. When an investor has a portfolio of such assets, they can be used as collateral when seeking financing for an LBO. This can lead to better financing terms, since the risk is reduced for lenders.

Tax Efficiency

You can offset interest expenses from the LBO debt against the taxable income. Concurrently, CRE investments offer depreciation benefits that can reduce taxable income further, leading to potential tax synergies.

Acquiring CRE through LBO

Leveraged Buyouts, while traditionally associated with corporate acquisitions, can also be used to acquire Commercial Real Estate assets. In fact, using an LBO structure can provide a powerful mechanism for real estate investors to acquire properties they might not afford otherwise. Below is a detailed examination of how you can use LBOs in the CRE realm:

Understanding the CRE LBO Structure

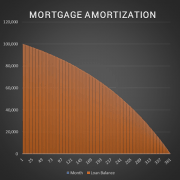

Just like in a traditional LBO, the basic structure of an LBO in real estate involves using a combination of equity and debt to acquire a property. The real estate asset itself often serves as the collateral for the loan. The rental incomes or cash flows generated by the property are then used to service the debt.

Steps in Using LBO to Acquire CRE

Identifying the Asset: Begin by identifying a potentially undervalued or income-generating property with stable cash flows. These cash flows will be crucial in servicing the debt.

Determining the Purchase Price: Once you identify the asset, negotiate a purchase price. It’s essential to conduct thorough due diligence and ensure there are no hidden liabilities or issues with the property.

Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV): Establish a legal entity, often a Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV), to hold your real estate asset. This entity is used to isolate the risks and liabilities associated with the specific investment.

Financing Structure: The hallmark of an LBO is its high debt-to-equity ratio. In a typical real estate LBO, the investor might put down 10% to 40% of the purchase price as equity, financing the rest with debt. The exact proportions can vary based on the risk of the asset, the investor’s relationship with lenders, and current market conditions.

Securing Debt: Approach lenders with a comprehensive proposal. Highlight the asset’s current and projected cash flows, its appreciation potential, and plans to improve its value.

Acquisition: Once you secure financing, proceed with the acquisition.

Managing and Increasing Property Value: This is a pivotal step. The primary goal post is to ensure the asset generates sufficient cash flow to service the debt. This might involve increasing rental incomes, reducing vacancies, or decreasing operational costs. Some investors might also invest in property improvements to further boost its value.

Exit Strategy: Just as in a traditional LBO, it’s essential to have a clear exit strategy. This could involve selling the property after a specified period, especially if its value has significantly increased. Alternatively, you could refinance to secure more favorable loan terms once the initial debt is reduced.

Benefits of Using LBO for CRE Acquisition

- By leveraging debt, investors can access and acquire properties that might be out of reach if entirely equity-financed.

- Given the high debt structure, any increase in the property’s value can lead to amplified returns in the equity of an investment.

- Interest payments on the debt can be tax deductible, leading to potential savings.

Risks and Considerations

- The property must consistently generate enough income to service the debt. Any significant vacancies or downturns in the rental market can jeopardize this.

- If you take the debt at a variable interest rate, spikes in rates can increase payment amounts.

- While leverage can amplify returns, it can also magnify losses. It’s essential to strike a balance and not over-leverage to the point where a minor market downturn leads to significant financial distress.

Maximum Debt Capacity

Traditional LBO Transaction

Determining the maximum debt capacity in an LBO transaction involves assessing the ability of the acquired business or asset to service the debt while still providing sufficient returns to equity investors. Various factors influence the debt capacity. Financial analysts use a range of financial metrics and ratios to evaluate the feasibility of the leverage structure. Here are some key considerations:

- A thorough analysis of the target company’s historical and projected cash flows. The ability of the business to generate consistent and predictable cash flows is crucial for servicing debt.

- Debt to EBITDA is a common metric used in LBO transactions to determine maximum debt capacity. Debt to EBITDA can be the average of companies operating in the same industry or line of business as of the target company, which may range from 4x to 6x.

- Type of debt can range from Senior Secured Debt to Unsecured and Mezzanine Debt. Lenders takes a bet on the cash flow generation capacity and value at exit to payoff debt.

- Consideration of debt covenants such as maximum debt to equity, minimum Debt Service Coverage Ratio, and minimum Interest Coverage Ratio, etc. imposed by lenders also plays a role in determining the level of debt.

CRE Acquisition Transaction

Banks determine the maximum Loan-to-Value (LTV) ratio in a CRE acquisition transaction based on a combination of factors to manage risk and ensure the loan is secured. LTV is a key metric that represents the proportion of the loan amount to the appraised value of the property. Here are some factors that banks typically consider when determining the maximum LTV in CRE acquisition transactions:

- Different property types carry varying levels of risk. Banks may have different LTV limits for office buildings, retail properties, industrial facilities, and residential developments. Riskier or less liquid asset types may have lower LTV ratios.

- The location of the property and the overall market conditions play a significant role. Banks may be more conservative in markets with higher volatility or lower demand and adjust LTV ratios accordingly.

- The creditworthiness of the borrower is a crucial factor. A strong credit profile may allow for a higher LTV ratio, as the bank may perceive a lower risk of default.

- The bank relies on a professional appraisal to determine the current market value of the property. The appraisal provides the basis for calculating the LTV ratio.

Similarities and differences in finding maximum debt capacity under LBO and CRE

There are some similarities and differences in finding the maximum debt capacity between Leveraged Buyout transactions and Commercial Real Estate acquisition transactions. Understanding these similarities and differences is crucial to navigate the models’ complexities and make informed decisions regarding financing and risk management.

Similarities

Cash Flow Analysis: Both LBOs and CRE acquisitions involve a thorough analysis of cash flows. In LBOs, it’s the cash flows of the acquired business. In CRE, it’s the property’s rental income and operating cash flows.

Debt Service Coverage Ratio (DSCR): DSCR is a critical metric in both types of transactions. It measures the ability of the acquired entity or property to cover debt service payments.

Risk Management: Both transactions require careful consideration of risks, including market conditions, industry trends, and specific risks associated with the target company or property.

Differences

Asset vs. Company Focus: In CRE acquisitions, the focus is on the underlying real estate asset. In LBOs, the focus is on the entire business, which may include various assets and operations beyond real estate.

Loan-to-Value vs. Debt-to-EBITDA: LTV is a primary metric in CRE acquisitions, representing the proportion of the loan amount to the appraised value of the property. LBOs emphasize the Debt-to-EBITDA, representing the debt relationship between and business earnings.

Business Operations and Value Enhancement: In LBOs, the debt capacity is linked to the ability to enhance the value of the business. In CRE, the focus is on the property’s inherent value and potential for income generation.

Equity Contribution: In LBOs, the equity contribution is typically a smaller percentage of the total transaction value, with the majority funded through debt. In CRE, the equity contribution may play a more significant role, and lenders may look for a higher equity cushion.

Exit Strategies: The exit strategies can differ. LBO exits may involve selling the entire business, while in CRE, exits could involve selling the property, refinancing, or repositioning the asset for better returns.

Conclusion

In a traditional CRE acquisition, the investor typically contributes a significant portion of equity, relying on debt financing to cover the remainder. Incorporating LBO principles into CRE involves maximizing the use of debt, thus minimizing the initial equity investment while aiming for higher returns. The financial flexibility inherent in LBO structures thus enables investors to allocate capital strategically.

Nevertheless, LBO structures cannot be used for every CRE Acquisition. Enhanced due diligence is required to determine the fair market value of the property, as undervalued properties with potential for growth are candidates for this strategy.

Overall, the LBO structure for CRE entails:

- Secure equity from investors, aiming for a smaller equity contribution compared to traditional CRE acquisitions.

- Secure debt financing from lenders. The goal is to secure a substantial portion of the purchase price through debt.

- Mezzanine financing can bridge the gap between the traditional mortgage amount and the total capital required. This allows for higher leverage while still adhering to the risk tolerance of senior lenders.

- Conduct a comprehensive cash flow analysis.

- Implement debt sculpting to tailor the debt repayment schedule to the property’s cash flow.

- Carefully size the debt to align with the property’s cash flow and the risk profile.

- Implement risk management strategies.

- Develop and execute a value enhancement strategy.

- Plan a well-defined exit strategy.

About the Author: Muhammad Shahzad Khan boasts a distinguished investment banking career spanning over two decades. Armed with a CFA Charter, Bachelor of Engineering, and MBA degrees, he has curated a unique track record marked by the successful structuring and execution of intricate investment banking transactions. His expertise spans diverse domains, including Leveraged Buyouts, Real Estate, and Infrastructure Project Finance.

Renowned for his prowess in financial modeling, Shahzad has held impactful leadership roles as the Head of Investment Banking, Chief Investment Officer, and Head of Syndication and Debt Capital Market at renowned financial institutions in Pakistan. He is currently serving as the Senior Manager – Debt Advisory and Capital Market at Ahli Bank in Oman and continues to contribute his strategic acumen and financial finesse in shaping the financial landscape in the region.