Deep Dive – Sources of Capital: Real Estate Private Equity (Updated July 2024)

Capital for commercial real estate investments is generally sourced from one or more of the following buckets: public equity, public debt, private equity, or private debt. In my experience, few people fully understand these four buckets of capital, let alone how the various capital sources work together to get a real estate deal done.

In this deep dive, one in a series of posts digging into complex topics in commercial real estate, I’ll discuss real estate private equity and how it fits into the broader real estate capital landscape.

What is Real Estate Private Equity?

From our glossary of commercial real estate terms:

“Real Estate Private Equity, or REPE, is a term used to describe an individual or firm making direct investments in real estate using private capital, rather than public capital. This form of investment in real estate is generally thought of as high risk, high return given that the invested capital is most often the first dollar in, and the last dollar out. A firm that raises private capital to make direct investments in real estate is referred to as a real estate private equity firm.”

Thus, when your neighbor Bob uses money in his personal bank account to buy the strip mall on the corner, he’s making a private equity investment in real estate. Similarly, when Blackstone, the world’s largest real estate private equity firm, uses capital from one of its opportunity funds to purchase an iconic skyscraper, that too is a private equity investment in real estate.

Download a few of the real estate Excel models private equity investors use to make direct investments in real estate

Private developers use their own capital (private equity) to get real estate developments out of the ground. Family offices use their own private capital, often passed down from previous generations, to purchase and maintain commercial real estate. Life insurance companies use capital from their balance sheet to make direct equity investments in real estate. And even pension funds and endowments have private capital – equity not sourced via the public markets – to invest in CRE.

In short, real estate private equity (REPE) – in its truest sense – is much more than just the opportunity funds managed by the Blackstones and KKRs of the world. The sooner you understand what real estate private equity is, in whose hands it’s held, and how it co-invests with other capital sources to make deals happen, the sooner you’ll land a job or raise capital from one of those firms.

How Private Equity Interacts with Other Capital Sources

Rarely does a deal get done without a combination of capital sources getting involved. Consider that 300-unit, mid-rise apartment project in your town.

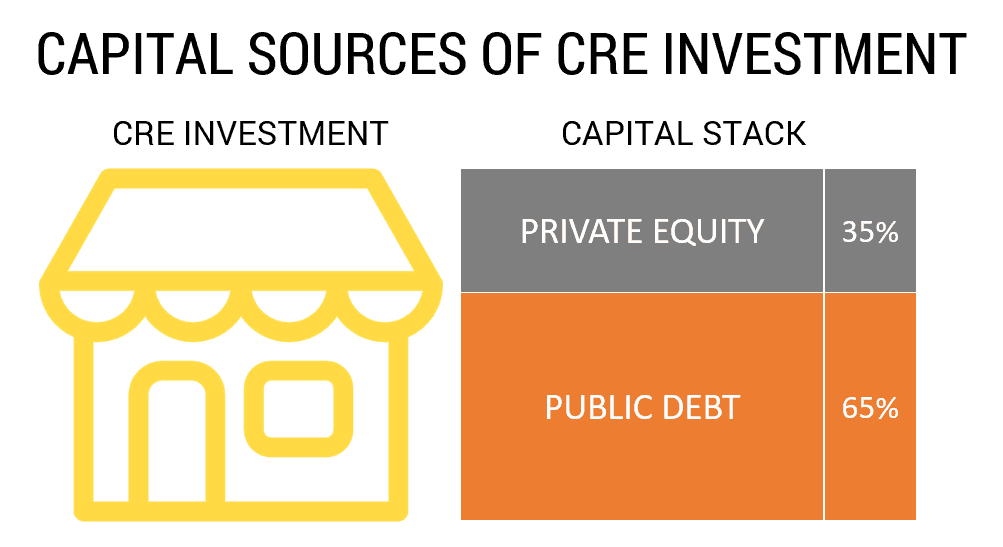

A local real estate developer (private equity) together with a capital partner (private equity) likely took out a construction loan with a commercial bank (private debt) to develop the project. The developer and capital partner likely committed 35% of the cost to develop the building, while the bank committed the other 65%.

Upon completion and once the building was fully leased, the developer and capital partner likely sold the building – let’s say to a public real estate investment trust (public equity). With the proceeds of the sale, the developer and capital partner paid off the construction loan.

While the real estate investment trust (public equity) used a line of credit to purchase the property, it needed a more permanent capital solution. So the real estate investment trust issued/sold common equity stock (public equity) to fund 50% of the acquisition, and then approached a life insurance company to provide a 10-year loan for the other 50% (private debt).

Example of the interaction between various capital sources in commercial real estate

After ten years, the apartment project is getting a little dated. Other newer and nicer projects have been built and so rents at the subject property have begun to lag the market. The real estate investment trust decides to sell the property.

A real estate investment sales team at your favorite national commercial real estate brokerage firm is engaged by the real estate investment trust to market the property. The team prepares an offering memorandum and markets the property as a value-add opportunity – buy, renovate, raise rents, and sell.

A real estate private equity firm (private equity), with a closed-end fund targeting apartment value-add opportunities, buys the building. The fund borrowers 65% of the in-place value from a CMBS lender (public debt), and then approaches a preferred equity investor (private equity) to provided an additional 25% of the capital. And thus, the cycle begins anew.

Interview with a Private Equity Investor – The Skyline Forum

To help illustrate what it means to be involved in real estate private equity, we’ve collaborated with a friend and fellow real estate aficionado, Ben Stevens. Ben is a project manager for a real estate development firm in Chicago. He recently graduated with an MBA in Real Estate and Urban Land Economics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. On the side, Ben hosts the The Skyline Forum, an online interview series with developers, architects, urban planners, and other real estate professionals.

In an episode of The Skyline Forum, Episode 12: All in Good Fund, Ben interviewed real estate private equity fund manager Dietmar Georg. Dietmar co-founded GLL Partners in 2000 in Munich, Germany, and has grown the company to a point where it now manages over $5 billion in real estate assets.

Ben has graciously given us permission to share the interview as well as a written transcript of the video. Ben’s interview with Dietmar does an excellent job of giving you a glimpse into the world of real estate private equity.

Read the Transcript of Ben’s Interview with Dietmar Georg

REPE (00:00 – 1:43)

Dietmar Georg: One of my coworkers here in Orlando is an asset manager in my firm. He had a seven, eight, nine year old daughter at the time and she was going to school and the nosy teacher in show and tell asked the daughter, “What does your dad do for a living?,” and the girl said, “Well, my dad plays Monopoly but with real money.” That’s as close as it gets to what we’re doing. The two exceptions are we don’t play with the money and it’s not our money, it’s other people’s money.

To give you an idea, a typical fund for us is 10 investors in all institutional investors putting up 50 million each gives you 500 million in equity. You put another 500 million in that on top of it and you bingo, have a billion dollar fund.

So then you have a club deal type of atmosphere where the investors know each other in the fund. It’s limited to 10 to 15.

Anything beyond that and you can’t call it a club deal anymore. There are funds, especially the Blackstone’s, the true private equity firms, that have hundreds of investors, but our deals are normally club deals, 500 million to a billion, maybe a little bit more.

Life of the REPE Fund (1:44 – 6:10)

Ben Stevens: So walk me through the development of a fund both in terms of the places where you seek opportunity, the places where you look for opportunity seekers, the people who’s money you’re gonna be investing, how you pitch to them.

Dietmar Georg: Okay, perfect. The life of a fund. Part one, idea generation, capital raising. Phase two is then the investment phase, the portfolio optimization phase, also called the holding phase, and finally, liquidation.

Let’s start with phase two. Most of these commingle close end funds are finite life and the finite life is almost all the time, nine out of 10 times a 10 year term. In that you have on average two years of acquisition investment to build the portfolio. Then you have roughly five years from years three to year eight or so of optimizing and asset managing the portfolio, getting the optimum value for the portfolio and then you have one to two years of liquidation.

So that’s the easy part. The part before that, idea generation, concept development, capital raising, from the moment somebody comes to senior management and says, “I have an idea for a new fund,” there is a window of opportunity in America right now or something, something. From that moment on, to having the capital raised, how long do you think that takes?

Ben Stevens: Probably 18 months to two years.

Dietmar Georg: You’re close. I have a timeline for this. If it’s a brand new fund, it will take 24 to 36 months.

The capital raising part is about one to two years of that, but it is easily one to one and a half years of work to get the fund to the point where you can raise the capital.

Ben Stevens: So when we talk about a 10 year fund, we’re not saying that these assets are held for 10 years. That’s the whole life of the project, so to speak?

Deitmar Georg: If it’s a 10-year finite life fund, then the assets are held from the moment they are acquired which is during the first two years. So they are on average probably held for eight to nine years.

What do you do if the liquidation phase happens to be, like in our first flagship fund in 2012, because we started our first fund in 2001 or 2002. At 10 years, when you get to the middle of the last financial crisis, was it a good time to liquidate assets? No, it was not. So we went back to the investors and said, “Hey, this is not the best time to liquidate,” and they gave us three more years.

From 2012 plus three, so it’s 2015 and we are right now liquidating the last of the assets.

Ben Stevens: Well, that’s good. Good timing.

Deitmar Georg: Yeah. It has worked out. It has worked out well for the investors and for GLL. What you have to create in fund management, one of the cardinal sins if you don’t do it, you have to create a no conflict of interest between the general partner and the limited partners. Everybody needs to pull on the same string and the fund manager must have the same incentive as the investors to sell at the best point in time.

We keep it fairly simple. It’s basically the fund manager gets 20 percent of the appreciation. So you have a billion dollar fund. If that in 10 years grows to two billion, let’s say one point five. Well, one point five billion, you have a 500 million capital gain. 20 percent of that is 100 million.

For the fund manager. That goes into the bonus pool, profit distribution and pays for all kinds of things. That’s why you really want to be part of this industry.

Raising Capital for a REPE Fund (6:11 – 8:16)

Ben Stevens: Talk to me about the process of going out, raising the capital, who you talk to and specifically how over the years you have learned to tailor your presentation to the kind of metrics and polish that they want.

Dietmar Georg: It’s a wide open field. I don’t even know where to start. Let me put it this way. We have learned over the years that you should create as homogenous an investor pool as possible. Ideally, 10 pension funds from the same country that have the same tax regime, the same currency exposure. You can mix and match pension funds and other institutions such as insurance companies, but you cannot probably put family offices or so in there. They have different return expectations and investment goals.

So that’s the first thing. You create a homogenous pool of investors, otherwise it’s going to be a disaster. You have to make a determination early on whether fundraising is part of your core competence in your own company or whether you want to farm out the fundraising.

That can be done today and there are specialist firms that probably originated on Wall Street. They’re called placement agents and for a fee, say anywhere between one and five percent of the equity raised, they will do it. You can mix and match. You can say, “Hey, I know the German institution investors. I know everyone there. I’ll do that myself, but I don’t know the Asian or Middle Eastern investors.”

Ben Stevens: So they don’t stipulate that it’s all or none. They’ll do whatever you ask.

Dietmar Georg: No, and you can have different placement agents in different regions.

Raising Capital in a Low Interest Rate Environment (8:17 – 11:34)

Ben Stevens: Okay. I’m interested and this is entirely tangential really to the interview, but what is your experience like raising capital in Germany? I just imagine the risk tolerance is very different and maybe it isn’t.

Dietmar Georg: It is. You put your finger right on it. Our investors are institutions, they are insurance companies, they are pension funds. They have a very low risk tolerance. That’s why we tend to offer the safest, most core type of investment funds.

We have ventured outside the core area, but we are really known as a core fund manager. Because that’s the nature of our capital.

Our investors to be happy in today’s environment, which is a very low interest and low cap rate environment, they’re getting on an annual basis, maybe five percent on a total return basis, maybe seven percent, and they have to compare that to less than one percent they’re getting on German fixed income.

A German bund just went negative. Negative. So why would they invest? They have these pension funds that traditionally have 60 percent of their portfolio in guilds or German bunds. Yeah, 10 year German treasuries. That’s not a win situation for them. So if we can deliver four or five percent or six percent to them…

Ben Stevens: Yeah, it’s exponentially higher.

Dietmar Georg: So the capital raising environment right now is good. Because institutions are allocating more to real estate than they have in the past.

Ben Stevens: How long, in terms of maybe half decade increments, do you think that these very low interest rates, I mean in Europe sometimes it’s negative, but in the States it’s also pretty low, is that a five, 10, 15, 20 year reality? What’s your guess?

Dietmar Georg: If I knew the answer, I wouldn’t be sitting here. I would be investing. It is an aberration what we have. The average 10 year treasury in the US over the last 30 years, forget the last five years of low interest, is probably six to seven percent.

And we’re now at one and a half percent in your treasury. That is manufactured by the federal reserve banks of this world. It is an aberration and it’s not normal.

It is the one big question that over hangs all of the discussions at real estate conferences and what have you. When will it end? I do not have the answer. I will tell you that I privately have bet the last three years against the fed and I’ve lost a lot of money. So I’m not the right person there to ask!

The Buy vs Develop Decision (11:35 – End)

Ben Stevens: One of the things that interests me the most is the way that we all get specialized. I’ve talked to developers about, “Well, why are you a developer? Why didn’t you do private equity,” and I’ve talked to private equity people, “Why didn’t you do development,” and the best advice I’ve heard is really it’s a market cycle thing. There are times when you could build brand new stuff for basically the same price or even less than you could buy stuff that’s already established, but there are other times when it doesn’t make any sense to build anything and there the whole metaphor of the used car comes in, “Why build something new? You could buy it just off the lot and it’s 25 percent cheaper.”

But it does seem to be a market cycle thing, like at certain times in the market, it’s better to buy, at certain times, it’s better to build, but then you have the problem that you specialize in one or the other even though it would on paper be better to develop at this point or buy at this point, you specialize. You’re a developer or you’re private equity.

Have there been many instances when you felt like, “Well, if all things were equal, I would rather be developing right now, but I’m in the buying business”?

Dietmar Georg: There have been instances, not many, but there have been. We are not developers.

But we have developed some in Eastern Europe, but not in the United States. But we had a wonderful opportunity in San Francisco. The building was to be torn down, a four story or five story 80, 90 year old building. Right in the center of development, the financial district was moving south right into that area. We had more than a half of year of discussion about whether we should develop this. We had the rights. We had the air rights. We had everything ready to go. All teed up.

And in the end, we decided not to do it. We learned something about our firm which is very important. We learned that our company does not have the developer gene. You have to have that gene.

Development is risk taking and is more art than science. We are more science guys, more numbers guys. I would have put my own money easily into that development. Well, we sold the whole thing ready to go, double ready, to a local developer. Made a tidy profit by just holding and selling.

Let’s say it was a two base hit, but it was not a grand slam.

The developer bought it and within two months had secured a 15 year lease for the whole building, build new, spec building. That is what is called a grand slam. So yeah.

Ben Stevens: So it’s a risk that everybody deals with.

Dietmar Georg: It is a risk and has it been tempting? Yes. But we’re doing well and we should maybe not get too greedy.

Conclusion on Real Estate Private Equity

I hope if you’ve learned nothing else from this post, it’s that real estate private equity is far more nuanced than what you might have initially thought. Private equity is in the hands of a lot more players than you might have supposed. And how that equity is allocated is largely driven by the risk appetite, investment strategy, and core competency of those holding that private equity.

And of course, another big thank you to Ben Stevens for his insightful interview with Dietmar Georg. I highly recommend you check out Ben’s The Skyline Forum series.

To continue expanding your knowledge of private equity and other commercial real estate concepts, consider checking out our A.CRE AI Assistant. This tool uses AI to provide personalized guidance, answer your CRE questions, and help you with financial modeling and analysis. Whether you’re a seasoned professional or new to the field, the A.CRE AI Assistant can enhance your understanding and efficiency.

Frequently Asked Questions about Real Estate Private Equity (REPE)

What is Real Estate Private Equity (REPE)?

Real Estate Private Equity refers to direct investments in real estate using private capital, rather than public capital. It is typically high risk, high return and involves being the first dollar in and last dollar out. It includes not just institutional funds, but also individuals and family offices investing privately in CRE.

Who participates in Real Estate Private Equity?

Participants include individuals, family offices, developers, life insurance companies, pension funds, and endowments. All use private (non-public) capital to make direct equity investments in real estate.

How does REPE interact with other capital sources?

Real estate deals often blend capital sources. For example, private equity may fund 35%, while a commercial bank (private debt) funds 65%. Later, a REIT (public equity) might purchase the asset using a mix of public equity and private debt, demonstrating how public and private capital work together in deal structuring.

What is the typical structure and life cycle of a REPE fund?

A REPE fund typically has a 10-year finite life:

2 years for acquisition,

5 years for optimization/management,

1–2 years for liquidation.

The capital raising and fund setup phase can take 24–36 months, especially for new funds.

How are fund managers compensated in REPE?

Fund managers typically earn 20% of the appreciation above a preferred return. For example, on a $500M gain, the fund manager may earn $100M. This incentivizes alignment with investor interests and encourages maximizing fund performance.

What is a “club deal” in private equity real estate?

A “club deal” is a small group of institutional investors—usually 10–15—that co-invest in a single fund. This structure fosters closer relationships and aligns investment goals across participants.

How do REPE firms raise capital for their funds?

Firms either raise capital directly or use placement agents who specialize in connecting with institutional investors. Fundraising typically involves building a homogenous investor pool with aligned risk and tax considerations.

How does market cycle affect REPE strategy?

Market cycles influence whether it’s more favorable to buy or develop. While REPE firms generally buy, some may consider development if it aligns with market timing and risk appetite. However, development requires a different mindset—more risk-tolerant and creative.

What happens if market conditions are poor at fund liquidation?

Funds can seek extensions from investors. For example, Dietmar Georg’s fund extended its life by 3 years beyond the original 10 to avoid liquidating during the global financial crisis, ultimately benefiting investors.